Practical 2

Last update: January 12th, 2026

Objectives

The learning objectives for this practical are:

- Have your computer set up to work with the Unix command-line.

- Download epidemiological data from the Catalan SIVIC network.

- Use a text editor to write your Unix scripts.

- Chain Unix commands using pipes.

- Extract rows and columns.

- Sorting lines.

- Counting occurrences.

- Pasting columns.

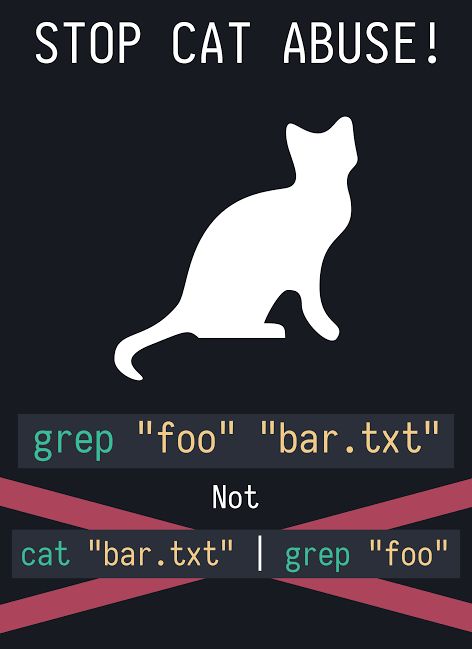

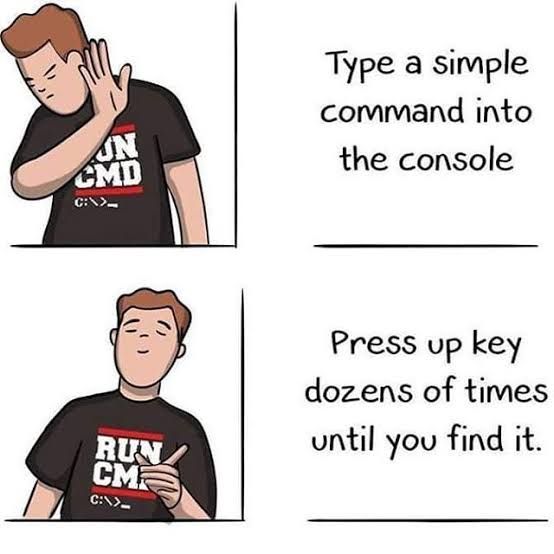

- Understand Unix command-line jokes.

Setup and background

In this practical we will use some basic commands to explore and manipulate text files in a Unix filesystem. You need to have access to a Unix command-line interface (CLI). If you are doing this practical in your own computer, please check the setup webpage to make sure that you have access to some flavor of a Unix operating system and its CLI.

Ideally, we would use the data files called

mostres_analitzades.csv and

virus_detectats.csv that were generated in the first practical, or download them again from the

SIVIC portal.

However, because those files currently store numerical values between

quotes as if they were text strings, you should directly download them

from the following links:

- Vigilància_microbiològica_sentinella_a_Atenció_Primària__mostres_analitzades_20240927.csv

- Vigilància_microbiològica_sentinella_a_Atenció_Primària__virus_detectats_20240927.csv

The version of these files available at those links were downloaded

from the Catalan SIVIC system on September 27th, 2024. Once you have

downloaded those two files, copy them into a fresh new directory called

practical2, and rename them to

mostres_analitzades.csv and

virus_detectats.csv, respectively.

Use a text editor to write your Unix scripts.

Unix commands can be combined into what is commonly known as shell scripts,

which are text

files containing a sequence of Unix commands that can be executed

one after the other. To create such shell scripts, you need to use a

text editor application. There are different types of text editors, some

of them listed at the setup webpage.

Here we recommend you using the Visual Studio Code text editor.

Once this text editor application is available in you computer, change

your current

working directory (CWD) to the previously created

practical2, and run the text editor as follows:

$ code practical2.shThis command will open the Visual Studio Code application and create

a new file called practical2.sh inside the

practical2 directory (if you really changed your CWD to

this directory). If you are using a different text editor, please adapt

the previous command accordingly. Once the text editor application is

running, write the following two lines:

## Script for practical 2

Save these contents using the File -> Save menu

option, or by pressing the Ctrl+S key combination (or

Cmd+S in MacOS). Make sure you save the file inside the

directory practical2 that you created before and verify

that the file is saved in that directory and has the contents you typed

by using the Unix commands ls and cat.

During the rest of this practical, write all the Unix commands that

you type in the terminal also in this text file, commonly known as

shell script file, practical2.sh. You don’t have

to type the Unix commands twice. First type the Unix command in the

terminal window and once the command works as expected, select the text

of the command using the mouse, and copy and paste it into the text

editor. Each time you copy a new line, save the file again. To keep a

better record of what you are doing, add above each shell line a shell

comment line, which always starts with one or more hash characters

(#), for example:

## list the files

lsOnce you have some Unix commands in your script file, and you have

saved it to disk, you may execute that script from the Unix shell as

follows (assuming you saved the script as

practical2.sh):

$ sh practical2.shChain Unix commands using pipes

In the previous practical we have seen how to redirect the terminal output to a file. In this section we are going to see a similar concept, where instead of redirecting the terminal output created by a Unix command to a file, we will redirect that terminal output as input into another Unix command by using what is known as a Unix pipeline, or Unix pipe for short. The concept of Unix pipes was created by Douglas McIlroy, which is based on his widely adopted view of the Unix philosophy:

Write programs that do one thing and do it well. Write programs to work together. Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.

To use the Unix pipe we should place the vertical bar character

(|) between the call to two commands. Tip:

In keyboards with a Spanish layout, the bar character | can

be written by pressing the keys AltGr+1 in windows and

Ubuntu, or Alt+1 in MacOS.

Try the following:

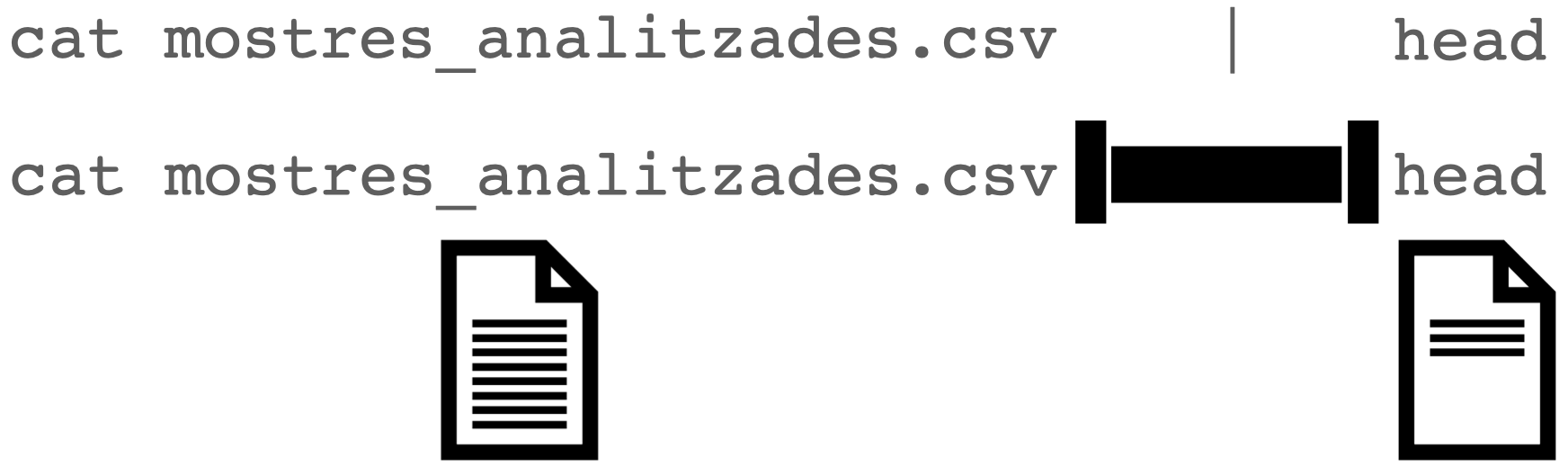

$ cat mostres_analitzades.csv | headNotice that while the cat command should have sent the

output of the whole text file to the terminal window,

we only see the first few lines of that output. This has occurred

because the pipe has sent that whole output from the

cat command to the input of the

head command, which only shows the first few lines of that

input. This can be graphically represented as follows:

Extract rows and columns

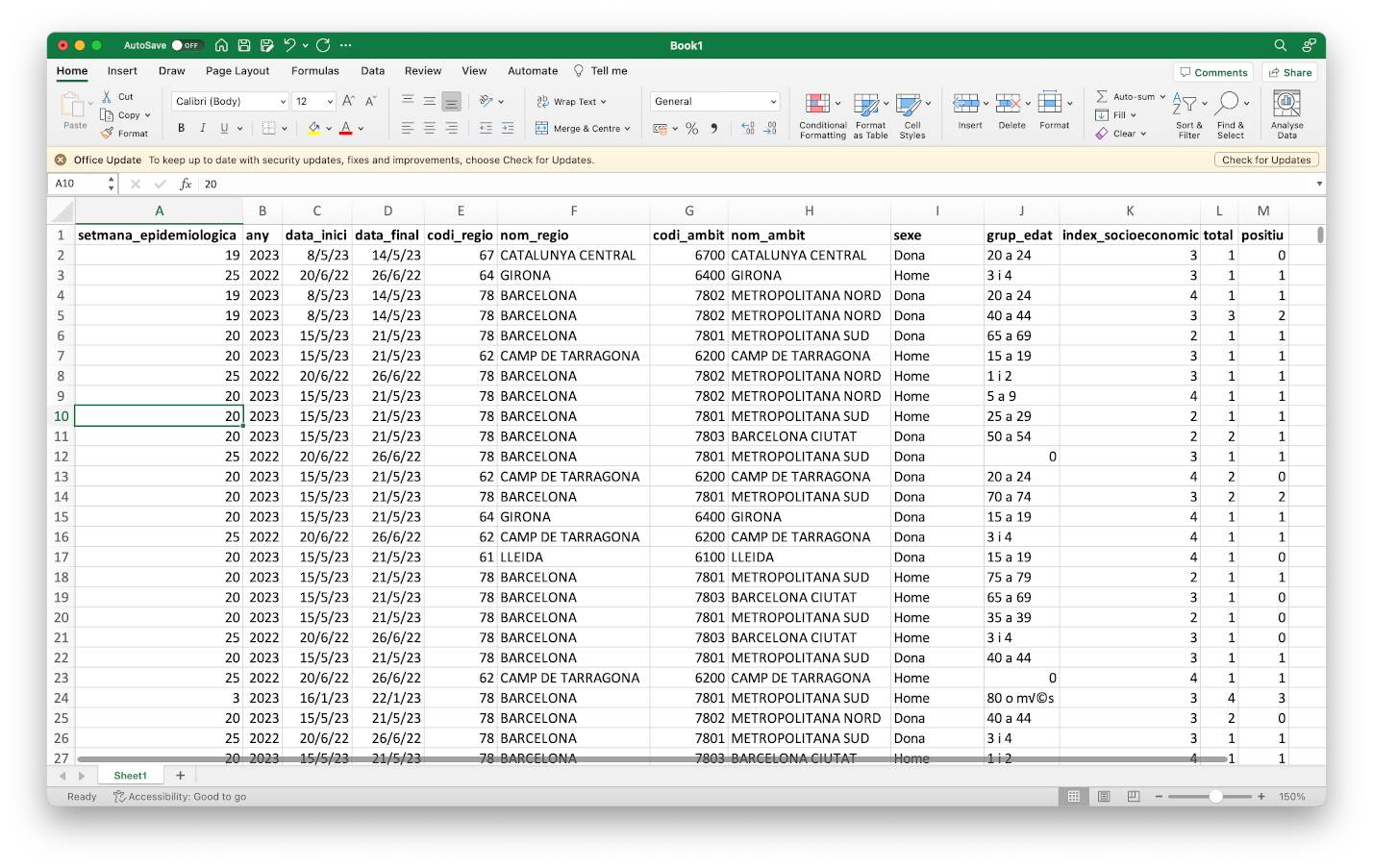

Text files such as CSV files have a matrix layout with rows

corresponding to lines and columns to values separated by some delimiter

character, which is a comma (,) in the case of the previous

file mostres_analitzades.csv. Because of its matrix layout,

a CSV file can be always opened by any spreadsheet software, such as

Microsoft Excel; see image below.

However, there are at least two circumstances in which working with CSV files from the Unix command-line is preferable to do it from a spreadsheet software such as Microsoft Excel:

- Spreadsheet software will always attempt to load the whole data into main memory. This may become prohibitive when having tens of thousands of rows, which is common for data with molecular-level measurements from high-thoughput instruments.

- Every spreadsheet software uses its own format to store the data, which makes it prone to digital obsolescence, the fact that old software required to open a file is no longer available. CSV files, and text files in general, can never become obsolete because their format does not depend on any specific software to be read or written.

Additionally, the misuse of Microsoft Excel has caused multiple problems with important consequences in loss of monetary and human-time resources, such as the loss in 2020 of COVID19-test results in England or the misspelling of gene names stored in Excel files as supplementary information to scientific articles.

Here we will learn to do two common operations on data organized in a

matrix layout: extract rows (lines) and extract columns

(delimiter-separated values). To extract rows from a text file in Unix

we will use the command grep, which requires two pieces of

information:

$ grep pattern filenamewhere pattern is the text that we expect to match to the

lines we want to extract, while filename is the name of the

file from which we want to extract the lines matching the pattern. Note

that pattern can be something sophisticated such as a regular

expression (not covered in this practical) and filename

can be ommitted when we want grep to read input from a

pipe.

For instance, the column nom_regio in the file

mostres_analitzades.csv stores the name of the Catalan area

to which the data in the row corresponds to. Let’s say we want to

extract the rows for the data derived from the area of Barcelona into a

separate file called mostres_analitzades_bcn.csv.

$ grep Barcelona mostres_analitzades.csv > mostres_analitzades_bcn.csvNow, repeat the command but this time extracting the rows

corresponding to the data derived from the area of Lleida into another

file called mostres_analitzades_lleida.csv.

Note: note that grep has worked well

for this particular task because any other column in the data that was

using the terms Barcelona or Lleida, had those

terms also in the column nom_regio. The grep

command doesn’t know about columns, it only finds

matches of a pattern in lines, reporting the lines that match the

pattern. You can also ask grep to report the lines that

do not match the pattern by using the option

-v.

Try to extract rows from the file

mostres_analitzades.csv with data corresponding to women

between 20 and 24 years of age into a new file called

mostres_analitzades_dones20a24.csv. If you are unsure how

to dump the output into a new file, please check this

section from the previous practical. Tip: when the

pattern consists of more than one word, or includes punctuation

characters, you should enclose the pattern between two quote characters,

e.g., 'something like this'.

Warning: when using the terminal output redirection

mechanism (>) you should never use as output

filename, the filename that is being used as input in the same command

line, because that would lead to overwriting the input file and

ending with a corrupted output or without output at all.

Extracting columns can be done using the Unix command

cut, which in the case of CSV files also requires

specifying the options -d and -f:

$ cut -d 'delimiter' -f field filenameThe option -d allows us to specify a delimiter character,

which by default is the TAB character and

should be always specified between single quotes (e.g.,

','). The option -f allows us to specify the

columns, also known as fields in this

context. For instance, let’s say we want to extract the column of the

CSV file mostres_analitzades.csv corresponding to the

number of positive cases at each week. First, we should identify which

position has this column in the first line:

$ head -n1 mostres_analitzades.csv

setmana_epidemiologica,any,data_inici,data_final,codi_regio,nom_regio,codi_ambit,nom_ambit,sexe,grup_edat,index_socioeconomic,total,positiuwhere we have used the option -n1 to force

head to show only the first line of the file. Then,

starting from 1, we should figure out that the column called

positiu is number 13 and taking into account that this file

uses the comma (,) as field separator, we should write the

following command-line to extract that column:

$ cut -d ',' -f 13 mostres_analitzades.csv | headNow let’s say we want to extract this column from the Barcelona subset of the data. We could either run the previous command on the file we created before:

$ cut -d ',' -f 13 mostres_analitzades_bcn.csv | heador had we not generated that file, we could have done it from the original data file using two pipes, as follows:

$ grep Barcelona mostres_analitzades.csv | cut -d ',' -f 13 | headNote that in both cases the output is identical.

Sort rows

Unix provides a command called sort to order rows of a

file in a number of ways. By default, it sorts rows in increasing

alphabetical order. Note for instance that in the

mostres_analitzades.csv file, the first column

setmana_epidemiologica contains the week of the year in

which the values for the corresponding row were obtained. However, if we

directly sort the file with the default regime of sort, we

will not see at the beginning of the data the first week of the year,

nor the last week at the end. Try the following:

sort mostres_analitzades.csv | head

sort mostres_analitzades.csv | tailTry now using the option -n, which forces

sort to output the lines in numerical order instead of the

alphabetical one and compare the result with the previous one:

sort -n mostres_analitzades.csv | head

sort -n mostres_analitzades.csv | tailNote: an important feature of the sort

command, and of most of the Unix commands, is that it leaves the input

file intact. The sort command merely shows

us the ordered version of the input file on the screen. It

does not alter the input file.

Exercise: generate an alphabetically increasing

ordered version of the file mostres_analitzades.csv and

store it under the file name

mostres_analitzades_ordenat.csv.

Remove consecutive duplicated lines

The Unix command uniq removes consecutive

duplicated lines. This command is mostly useful in combination

with the previous two commands that can be used to extract a column and

sort it alphabetically, because that operation will allow us to output

identical values together. Let’s see this working with the following

example on the file mostres_analitzades.csv, try to

understand what is each command line doing:

$ cut -d ',' -f 6 mostres_analitzades.csv | head

nom_regio

Camp de Tarragona

Camp de Tarragona

Barcelona Metropolitana Sud

Penedès

Girona

Penedès

Penedès

Camp de Tarragona

Barcelona Metropolitana Sud

$ cut -d ',' -f 6 mostres_analitzades.csv | sort | head

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Alt Pirineu i Aran

$ cut -d ',' -f 6 mostres_analitzades.csv | sort | uniq

Alt Pirineu i Aran

Barcelona Ciutat

Barcelona Metropolitana Nord

Barcelona Metropolitana Sud

Camp de Tarragona

Catalunya Central

Girona

Lleida

No disponible

nom_regio

Penedès

Terres de l'EbreCount consecutive occurrences

In the previous practical, we have seen the command wc,

which can be employed to count the lines of a text file. Here we will

see that the command uniq with its option -c,

can be used to count consecutively repeated lines. This

is useful to count occurrences of interest in a file. For instance,

let’s say we want to count the number of different occurrences of

positive cases in the file mostres_analitzades.csv, i.e.,

how many lines (weeks) reported 0 positive cases, how many reported 1,

how many reported 2, etc. We need to extract the positive column (13),

sort it and apply the uniq -c command (results below from

data downloaded on September 27th, 2024):

$ cut -f 13 -d ',' mostres_analitzades.csv | sort | uniq -c

6942 0

13452 1

1 10

1 12

2658 2

626 3

147 4

41 5

12 6

8 7

5 8

1 positiuLet’s say we want to see the most frequent occurrences first. We

would need then to sort the previous output numerically (option

-n) and from largest to smallest (option -r),

as follows:

$ cut -f 13 -d ',' mostres_analitzades.csv | sort | uniq -c | sort -n -r

13452 1

6942 0

2658 2

626 3

147 4

41 5

12 6

8 7

5 8

1 positiu

1 12

1 10So the most frequent reported positive figure was 1 in 13452 weeks

(lines in the CSV file), the second most frequent one was 0 positives in

6942 lines, and so on. We can also tell sort to order that

output by the second column using the option -k, where we

should specify the range of columns (separated by a comma ‘,’) we want

to use for ordering), which would give us the whole ordered frequency

distribution of positives:

$ cut -f 13 -d ',' mostres_analitzades.csv | sort | uniq -c | sort -n -k 2,2

1 positiu

6942 0

13452 1

2658 2

626 3

147 4

41 5

12 6

8 7

5 8

1 10

1 12Paste columns

The Unix command paste allows us to paste in parallel

lines of given files using a TAB as delimiter character by

default, which can be changed with the option -d. For

instance, see what happens when extract two columns from the CSV file

and paste them again:

$ cut -d ',' -f 1 mostres_analitzades.csv > mostres_analitzades_setmana.csv

$ cut -d ',' -f 13 mostres_analitzades.csv > mostres_analitzades_positiu.csv

$ paste mostres_analitzades_setmana.csv mostres_analitzades_positiu.csv | head

setmana_epidemiologica positiu

12 1

44 0

32 1

27 0

42 1

11 1

22 0

4 0

35 1Exercises

Using the Unix commands we have learned in this practical, try to

answer the questions below about the downloaded SIVIC data. Try to edit

a shell script for each question under the filename, for instance,

question1.sh, question2.sh, etc., and execute

it from the shell as, for instance:

$ sh question1.shQuestion 1

One of the previous commands revealed a value called

No disponible, which suggests that some of the weeks in the

two SIVIC data files, may contain the so-called missing values.

Calculate how many weeks do we have in each of the two SIVIC data files,

mostres_analitzades.csv and

virus_detectats.csv, excluding those with missing values.

(answer: 23793 for mostres_analitzades.csv and 21394 for

virus_detectats.csv, for the data downloaded on September

27th, 2024)

Question 2

Which was the highest number of positives in the file

mostres_analitzades.csv in the data from the last week of

2022? (answer: 5 for the data downloaded on September 27th, 2024)

Question 3

Using the file virus_detectats.csv, figure out how many

different viruses are being tested by the SIVIC system. (answer: 10 for

the data downloaded on September 27th, 2024)

Question 4

Using the file mostres_analitzades.csv, build a ranking

of the data by the number of positives cases, from highest to lowest,

found in the area of Lleida in 2022, among men between 40 and 44 years

of age, showing only the week number, initial and end date, and number

of positives. For the data downloaded on September 27th, 2024, the top

of the ranking should look like this:

46,14/11/2022,20/11/2022,5

47,21/11/2022,27/11/2022,2

40,03/10/2022,09/10/2022,2

51,19/12/2022,25/12/2022,1

50,12/12/2022,18/12/2022,1

48,28/11/2022,04/12/2022,1

46,14/11/2022,20/11/2022,1

45,07/11/2022,13/11/2022,1

45,07/11/2022,13/11/2022,1

41,10/10/2022,16/10/2022,1Question 5

Generate the ranking from the previous question replacing the area of Lleida by the area of Girona and compare the top of those two rankings, side by side. For the data downloaded on September 27th, 2024, the top of that comparison should look as follows, with the data from Lleida on the left and from Girona on the right:

46,14/11/2022,20/11/2022,5 22,30/05/2022,05/06/2022,3

47,21/11/2022,27/11/2022,2 50,12/12/2022,18/12/2022,2

40,03/10/2022,09/10/2022,2 42,17/10/2022,23/10/2022,2

51,19/12/2022,25/12/2022,1 39,26/09/2022,02/10/2022,2

50,12/12/2022,18/12/2022,1 52,26/12/2022,01/01/2023,1

48,28/11/2022,04/12/2022,1 51,19/12/2022,25/12/2022,1

46,14/11/2022,20/11/2022,1 49,05/12/2022,11/12/2022,1

45,07/11/2022,13/11/2022,1 46,14/11/2022,20/11/2022,1

45,07/11/2022,13/11/2022,1 45,07/11/2022,13/11/2022,1

41,10/10/2022,16/10/2022,1 40,03/10/2022,09/10/2022,1We can observe that both areas had the larger occurrence of positives cases around the same weeks of the year, except for the 22nd week in Girona.

Question 6

Can you understand the following Unix command-line jokes?